|

In the latest of articles from our freelancers on certain areas of law, and following our articles on intellectual property and copyright, this article looks at the basics of trademarks and includes some helpful tips to think about. As always, it is worth restating that HPLpro is not a legal firm (we supply freelance in-house lawyers), and this article should not be taken as legal advice. It is important for you and your business to have experienced legal practitioners review your business ideas and intellectual property portfolio to ensure that they adequately meet your needs. Please feel free to request a freelance in-house lawyer from us if required. All of the trademarks used in this article are used without permission, no challenge to their status intended.

|

|

Top tip #1 – When creating a new brand or a new product, or even if you are setting up a new company and you are considering the company name, it is absolutely worth checking whether someone else has registered that mark, or a similar mark, by doing a trademark search. You can do this either by engaging an expert such as a lawyer to do the search for you, or you can do it yourself online, normally by accessing the relevant government department website for your country (although given that there can be an element of complexity to some marks, we would always encourage you to go to an expert). For example, in the UK, you would use the UK Intellectual Property website. In the US, you would go to UPTSO, the United States Patent and Trademark Office. Doing such searches up front can save you time and money in the long run by avoiding potentially ruinous litigation. |

Registered/non-registered trademarks

Trademarks can either be registered or unregistered depending upon the territory and the owner of the mark will have different remedies available depending upon the registration.

If the territory that you are doing business in recognises unregistered trademarks, you will start to get the benefit of upon starting trading with that mark. Most of the time, the more trading that you do, the more reputation the mark will build, and the stronger your claim of ownership will be – there are some complications which are outlined later in this article.

In respect of registrations, there is no global register of trademarks, but some countries do have collective registrations, such as the European Union. This means that you can register a trademark under the European system and get protection in all of the EU countries. Of course, registering comes with a cost and you can either register a mark through a lawyer or agent, or you can do it directly on the webpage for the relevant country registrar. In the US, a trademark registration typically costs between $200-400 per mark per class. In the UK it costs between £170-200 and then there is an additional but lower cost of £50 for additional classes for the same mark. Be aware that these costs can, and do, change. In addition, trademarks need to be renewed meaning that after every ten years or so (depending upon the territory) there is more cost.

If the territory that you are doing business in recognises unregistered trademarks, you will start to get the benefit of upon starting trading with that mark. Most of the time, the more trading that you do, the more reputation the mark will build, and the stronger your claim of ownership will be – there are some complications which are outlined later in this article.

In respect of registrations, there is no global register of trademarks, but some countries do have collective registrations, such as the European Union. This means that you can register a trademark under the European system and get protection in all of the EU countries. Of course, registering comes with a cost and you can either register a mark through a lawyer or agent, or you can do it directly on the webpage for the relevant country registrar. In the US, a trademark registration typically costs between $200-400 per mark per class. In the UK it costs between £170-200 and then there is an additional but lower cost of £50 for additional classes for the same mark. Be aware that these costs can, and do, change. In addition, trademarks need to be renewed meaning that after every ten years or so (depending upon the territory) there is more cost.

In respect of what can actually be registered, this will change from territory to territory, but commonly, registrations will cover words, phrases and/or logos. In addition, as stated above, certain jurisdictions also permit colours and sounds to be registered although those registrations are not the easiest to obtain. See the section on restrictions below for what cannot be registered.

Recently, in the UK, Nestle were denied their application to register the above choclolate shape as a trademark (on account of it not being distinctive enough)

An unregistered trademark is denoted by the ™ symbol next to the mark, whereas a registered trademark is denoted by the ® symbol. Have a look at the above well-known examples.

|

Top Tip #2: In Microsoft Word – and probably other word processing software - if you type in left bracket, the letters 'tm' and a right bracket, the character ™ will appear; and if you type in, left bracket, the letter 'r' and a right bracket, the character ® will appear |

Trademark classes

Further, to complicate things slightly, trademarks exist in 'classes' which is a way of dividing those marks into categories of use. For example, Class 34 refers to tobacco and articles for smoking. That means that HPLpro could own a trademark for the word 'Cobra' in class 34 and that mark is not likely to infringe a 'Cobra' word trademark in class 39 – transport.

The Nice Classification (NCL), established by the Nice Agreement (1957), contains a list of the internationally recognised trademark classes (searchable on the World Intellectual Property Organisation webpage).

The process of trademark registration can take a while, particularly if any other individual or company objects to that registration. For example, if you try to register the trademark 'Red Bullock' in class 32 (Beer and Beverages) your application is likely to receive and objection by a certain manufacturer of energy drinks. As stated in toptip#1 if you have created a new product you should always perform a trademark search prior to releasing that product or registering a trademark.

The Nice Classification (NCL), established by the Nice Agreement (1957), contains a list of the internationally recognised trademark classes (searchable on the World Intellectual Property Organisation webpage).

The process of trademark registration can take a while, particularly if any other individual or company objects to that registration. For example, if you try to register the trademark 'Red Bullock' in class 32 (Beer and Beverages) your application is likely to receive and objection by a certain manufacturer of energy drinks. As stated in toptip#1 if you have created a new product you should always perform a trademark search prior to releasing that product or registering a trademark.

Trademark strategy

If your company has a large trademark portfolio, costs can sometimes mount up very quickly. You should ask yourself, do you need to register everything? Unfortunately, when it comes to trademark strategy, many companies (and indeed lawyers) advocate the approach of registering everything that can be registered.

One of our freelancers has worked for a company where the approach was to register absolutely everything in every class they possibly could, which amounted to a portfolio of 3000 trademarks each in at least 4 classes. That is a very, very expensive endeavour. Registering a mark is fairly futile if you do not intend to protect that mark, which means that the costs of bringing trademark infringement claims also need to be considered in any IP strategy. Having an all-encompassing trademark registration strategy can be extremely costly.

Of course, sometimes it is necessary for certain business in certain industries to have such as wide approach and each business should certainly talk to a professional to assess their specific needs. Nevertheless, such a strategy should consider what is important for that business and register those marks in the classes that you will use. This exercise cannot be done in isolation, consideration should be given to the industry as a whole, competitor activity, as well as likely future trading activity. If you would like to engage a HPLpro freelancer to help you with you trademark and/or IP strategy do let us know.

One of our freelancers has worked for a company where the approach was to register absolutely everything in every class they possibly could, which amounted to a portfolio of 3000 trademarks each in at least 4 classes. That is a very, very expensive endeavour. Registering a mark is fairly futile if you do not intend to protect that mark, which means that the costs of bringing trademark infringement claims also need to be considered in any IP strategy. Having an all-encompassing trademark registration strategy can be extremely costly.

Of course, sometimes it is necessary for certain business in certain industries to have such as wide approach and each business should certainly talk to a professional to assess their specific needs. Nevertheless, such a strategy should consider what is important for that business and register those marks in the classes that you will use. This exercise cannot be done in isolation, consideration should be given to the industry as a whole, competitor activity, as well as likely future trading activity. If you would like to engage a HPLpro freelancer to help you with you trademark and/or IP strategy do let us know.

We have Pepsi, would you like one?

Unlike other forms of IP, trademarks need to be maintained as they can be damaged by a trademark owner. Trademarks, if misused, can actually bring about their own downfall. For example, if a trademark becomes generic it can actually be challenged. I am sure that we have all been in a restaurant and asked for a Coca Cola only to be met with, "we have Pepsi, would you like one?" (or vice versa).

Such a question is asked to ensure that trademarks maintain their distinctiveness. Some people suggest that having a mark that is so powerful it is used in relation to products that are not your own is a positive thing for a business – they argure that it means that the business 'owns' the space for that product. Nevertheless, the issue becomes of vital importance when a business with a generic trademark attempts to stop a third party from using it commercially – they may not be able to. Indeed, their own mark may be found to be invalid for lack of distinctiveness.

Thermos, Kleenex, and Hoover are all examples of genericized trademarks.

Of course, the most powerful trademark at present that is arguably at risk of becoming generic is Google. Googling anyone? Whenever somebody says 'google it,' to you do you only use the Google search engine or do you use any search engine available?

To ensure that your marks maintain their distinctiveness, even when they become globally popular, you must ensure that you always use your trademarks consistently, educate your customers the correct way to use the marks through your marketing (rather than reinforcing bad habits) and always challenge misuse of those marks. Also, avoiding the use of the mark as a verb will help (such as Hoovering or Googling). Finally, using the mark adjacent to the generic type of goods or service will likewise assist in prevention of genericization: for example, Burger King burgers, Sprite soft drink, Bud Light beer.

When thinking up names for new brands and the like there are three main schools of thought: use a name which indicates to customers what the brand could be (e.g. Pizza Hut); use a name which is a real word but normally used in a different context (e.g. Apple) and think up a completely new word (e.g. Google). It is perhaps not a coincidence that many of the strongest global marks take the latter approach. Any marks that come in the first category are going to have a hard time proving that they are distinctive enough to be registered (see below).

Such a question is asked to ensure that trademarks maintain their distinctiveness. Some people suggest that having a mark that is so powerful it is used in relation to products that are not your own is a positive thing for a business – they argure that it means that the business 'owns' the space for that product. Nevertheless, the issue becomes of vital importance when a business with a generic trademark attempts to stop a third party from using it commercially – they may not be able to. Indeed, their own mark may be found to be invalid for lack of distinctiveness.

Thermos, Kleenex, and Hoover are all examples of genericized trademarks.

Of course, the most powerful trademark at present that is arguably at risk of becoming generic is Google. Googling anyone? Whenever somebody says 'google it,' to you do you only use the Google search engine or do you use any search engine available?

To ensure that your marks maintain their distinctiveness, even when they become globally popular, you must ensure that you always use your trademarks consistently, educate your customers the correct way to use the marks through your marketing (rather than reinforcing bad habits) and always challenge misuse of those marks. Also, avoiding the use of the mark as a verb will help (such as Hoovering or Googling). Finally, using the mark adjacent to the generic type of goods or service will likewise assist in prevention of genericization: for example, Burger King burgers, Sprite soft drink, Bud Light beer.

When thinking up names for new brands and the like there are three main schools of thought: use a name which indicates to customers what the brand could be (e.g. Pizza Hut); use a name which is a real word but normally used in a different context (e.g. Apple) and think up a completely new word (e.g. Google). It is perhaps not a coincidence that many of the strongest global marks take the latter approach. Any marks that come in the first category are going to have a hard time proving that they are distinctive enough to be registered (see below).

Restrictions

Be aware that there will be some things that you cannot trademark and this list of restrictions will differ depending upon what territory you are in. A trademark that has been registered can also been found to be invalid if it breaches such restrictions. You need to have a look at the website of the relevant registrar or talk to an expert to find out what the restrictions are in in your jurisdiction.

Common restricted marks may include:

Common restricted marks may include:

- marks which give the impression of government association or approval (or royal approval in the UK);

- Geographical locations – although geographical locations are rarely owned by one business, nevertheless they can be exploited only by businesses operating in that area (Melton Mowbray pork pies, for example);

- generic/non-distinctive marks (see above);

- certain flags, emblems;

- marks which are too similar to other marks; and

- obscene marks.

We hope that you found the above useful. Let us know if you have any questions or if you have a need for part-time or temporary in-house legal support.

The HPLpro team

Comments

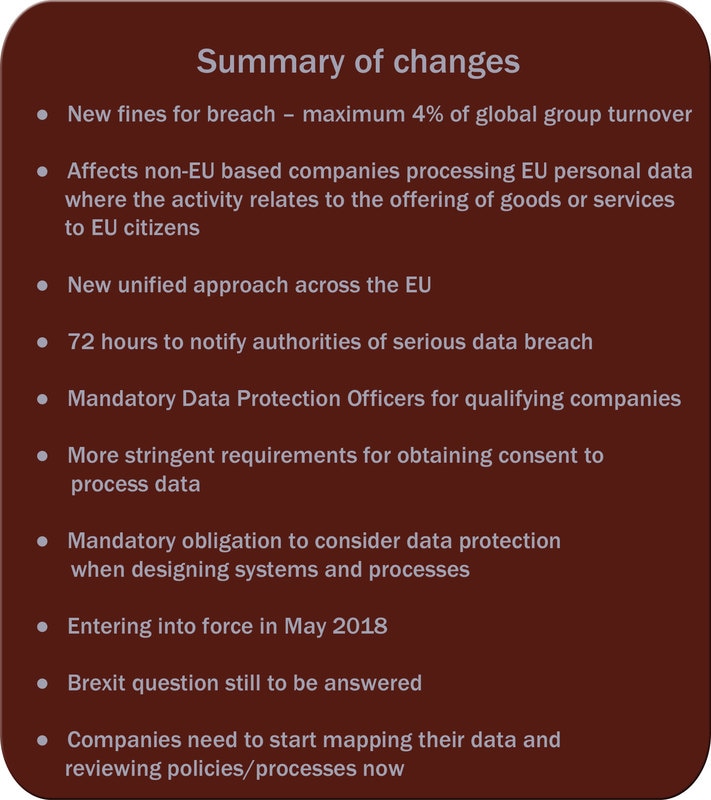

Some people find data protection a very dry (or even boring) subject. However, we would urge those people, particularly if you are in a position of management in a company, to bear with us, if only for this article, as data protection within the EU is just about to get a lot more interesting/serious – see the summary box below as to why. HPLpro can of course provide a freelance in-house lawyer to help you with your data protection requirements on a part time, short-term or project by project basis. We will post more articles on this subject as we get nearer to the implementation date.

As always, it is worth restating that HPLpro is not a legal firm, and this article should not be taken as legal advice. It is important for you and your business to have experienced legal practitioners advise you upon the data protection regulations to ensure that you are adequately prepared.

We will repeat this later in the article but it is worth saying up front as it will grab the most attention, the new fines for the most serious data protection breaches can be up to 4% of global turnover. Yes, that is turnover not profit. In terms of legislative 'bite', this means that EU data protection regulation now has the same teeth as EU competition law regulations. In other words, if you are not doing so already, it is now time to start taking this subject very seriously.

What is data protection?

Very briefly, data protection is regulation which governs how companies use, store and process the personal data of EU citizens, personal data being defined as any data that can directly or indirectly identify an individual. The European Commission lists some examples as: "name, a photo, an email address, bank details, your posts on social networking websites, your medical information, or your computer's IP address."

Given that a fairly sizable change is on the horizon, we will not cover the current data protection position in any detail in this article.

Given that a fairly sizable change is on the horizon, we will not cover the current data protection position in any detail in this article.

So, what is changing then?

The new piece of EU law is the General Data Protection Regulation. Notice firstly, that this is a regulation rather than a Directive, meaning that it is automatically imported into EU Member State law – unlike with the old Directive where those Members States had to enact their own legislation to bring the Directive into force in their country. This means that the new law will be the same across the whole of the EU. The new Regulation applies from 25-05-2018.

What do I need to know about the new rules?

Penalties

Previously, reputational damage was arguably the biggest risk to a company breaching data protection regulations. Fines did exist and have been used - regularly - but those fines amounted to hundreds of thousands of pounds at the top end (the largest being £400,000 to mobile telecoms provider Talk Talk). As stated above, things are about to change dramatically in this area. Under the new regulations, organisations in breach can be fined up to a maximum of 4% of annual global turnover or Twenty Million euros (whichever is the greater). For clarity, if your company is a subsidiary in a global group, the fine is 4% of the group turnover. Such fines are likely to be reserved for the most serious breaches of the regulations such as big personal data leaks, not having proper consent from individuals for processing and not putting data protection at the heart of designing new systems and processes.

Who the regulations apply to

The new regulations apply to so called 'controllers' and 'processors' of personal data where the controller is the party directing the processor why and how the data needs to be processed. A company can of course be a processor and a controller at the same time. For the sake of ease, this article will refer solely to the term data processors for both types of entity.

Extra territorial scope

The new regulations apply to: any EU based entity processing the data of EU citizens (wherever in the world that data is processed) and no matter whether that company is processing data on behalf of another company; and it will also apply to the processing of personal data of EU subjects by a non-EU processor, where the activities relate to: offering goods or services to EU citizens and the monitoring of the behaviour of EU citizens. Additionally, Non-EU businesses processing the data of EU citizens will have to appoint a representative in the EU.

Getting consent

The regulations demand that the processing of personal data requires the consent of the subject of that data. Further, that consent must: be unambiguous; be obtained using clear and understandable language; relate to the purpose that the data will be used for; and it must be just as easy to withdraw the consent as to give it. For sensitive personal data, the bar is set even higher with opt ins being required (sensitive data consists of things such as the subject's religious beliefs, sexual practices, political opinions, racial origin, mental health and so on). If you have mailing list tick boxes, you need to reconsider whether they are fit for purpose in light of these changes.

Notifying authorities when a breach occurs

Where a data breach occurs that is likely to, “result in a risk for the rights and freedoms of individuals,” data processors now have a mandatory obligation to notify the regulatory authorities. In fact, this has to be done within 72 hours of the processor becoming aware of the breach. In certain circumstances, data processors will also be required to directly notify their customers “without undue delay”. Guidance from the regulatory authorities on any threshold for notification and what breaches will constitute “a risk for the rights and freedoms of individuals,” is expected to be forthcoming and we will write a further article to clarify when that guidance is released.

Right to access data/portability

The regulations also increase the ability of data subjects to access data that an entity holds on them including a requirement for the processor to supply a copy of that data, free of charge, in an electronic format. Further, the data subject can now request the information in a common format to enable it to be transferred to another data processor.

Right to be Forgotten

The ability to be forgotten by data processors has been in the news over the last few years but now the regulations will address the issue; specifically, this right enables data subjects to require processors to erase their personal data and cease further use of it provided certain conditions have been met (such as the data no longer being required or consent to processing being withdrawn). When considering such requests, data processors have to consider the individual's rights in relation to "the public interest in the availability of the data" and, presumably, detailed guidance will be forthcoming at some stage in respect of how to do that.

Privacy by Design

Entities now have an overt obligation to consider data protection when they build new systems and policies. For example, the regulations require data processors to only hold data only for as long as it is necessary to complete its duties and access to personal data must be limited to only those persons who actually need it.

Data Protection Officers

Public authorities and entities that engage in large scale systematic monitoring or processing of personal data now also have to have an employee responsible for ensuring that the regulations are complied with – a Data Protection Officer. Companies that do not fall into these categories will not have to have such an employee but those companies will nevertheless do well to consider how they are going to ensure compliance with the regulations without an individual overseeing the whole programme. A data protection officer can be an employee or an external service provider (such as an HPLpro freelance lawyer) and must be appointed on the basis of professional qualities and, in particular, expert knowledge on data protection law and practices – it will not suffice to simply give an employee the title of data protection officer in order to comply with the regulations. Interestingly, the regulations require that data protection officer to report to the highest level of management in an entity and prevents that officer from doing any tasks which may conflict with their duties as data protection officer. Again, it is worth repeating that this applies to processors of EU data for goods and services or monitoring, no matter where in the world they are based.

What should we be doing now to prepare?

The chances are that most companies and entities have not done enough in respect of getting prepared for the change so there is probably an enormous amount left to be done over the next 12 months. Take a look at the below infographic, produced by the UK information Commissioner's Office, which shows you how prepared UK local government authorities are for the regulations. This is fairly alarming considering local authorities have to comply with some of the most rigorous elements of those regulations.

Below are some activities that your company can start doing now in anticipation of the 2018 deadline.

Talk to the Board/CEO/GM/MD/VPs

Achieving compliance with the regulations, particularly for a large entity, is unlikely to be a quick and easy affair, indeed, it will most certainly take time and commitment from employees who are undoubtedly busy with other matters meaning that it will also likely take money. In that sense, it is imperative that the boards of companies buy in to the importance of data protection and treat it as seriously as they would competition law, bribery and corruption, health and safety and environmental regulations. This topic should be raised with the board of companies as soon as possible if it has not already been done, particularly by (if a company has any) the in-house lawyers, IT Security personnel and compliance officers. We anticipate that this will significantly impact EU companies that have US parent companies and the boards of those parent companies should be alerted as soon as possible. A company that takes its data protection obligations seriously will undoubtedly be viewed differently to a company that is dismissive, reckless or negligent in its approach to data protection.

Get a map

The most important thing is to know where you currently stand in relation to the data that you hold and data that you need now and data that you will need when the regulations come into force in 2018.

In other words, you need to map your data – where is it, who touches it, what system is it on, how secure is it, who has access, what do they do with it and so on and so forth. Remember, this is for any data that can identify an individual – going back to the European Commission's list of examples that can include: " name, a photo, an email address, bank details, your posts on social networking websites, your medical information, or your computer's IP address." If that sounds like a daunting task, just remember that the penalty for getting this wrong could be as high as 4% of the global turnover of the corporate group.

In other words, you need to map your data – where is it, who touches it, what system is it on, how secure is it, who has access, what do they do with it and so on and so forth. Remember, this is for any data that can identify an individual – going back to the European Commission's list of examples that can include: " name, a photo, an email address, bank details, your posts on social networking websites, your medical information, or your computer's IP address." If that sounds like a daunting task, just remember that the penalty for getting this wrong could be as high as 4% of the global turnover of the corporate group.

Review the required consents

Once you have mapped your data, you will need review it to ensure that that data and that use has the appropriate level of consent from the people that the data relates to as required by the legislation and that the consent, if required, is easily evidenced and accessible. If not, you should take steps now to ensure that you have the mechanisms in place to obtain the appropriate levels of consent; there is no need to wait until the deadline to ensure that your consent database is fit and healthy.

Data Access requests

You will need to ensure that your business has an adequate system for processing data access requests as and when they arrive. Given that companies can no longer charge for such requests, it will likely be more cost effective to have a robust, easy to use system and/or process in place prior to any request coming in.

Review your contracts

You should examine all of your contracts to ensure that any party holding data on your behalf has the appropriate obligations in those contracts to ensure that your company does not fall foul of the regulations. Additionally, such requirements should be backed up by strong indemnities and warranties to provide appropriate remedies and emphasise the importance of compliance to your company.

Train your people

Awareness campaigns and training programmes should be established now so that by the time the regulations land, the principles therein are common place within your business and are part of your business culture. Culture, of course, comes from the top (see the ' talk to the Board' section above).

Data Breach checklists and tests

What would you do if your company suffered a significant data breach? Having a policy to follow will minimise any missteps in the process, bearing in mind that there is a 72 hour clock to notify that starts ticking. It is perhaps worthwhile having a 'dry run' data breach exercise in order to expose flaws in your present systems and policies. Data breaches, and the regulatory assessment of those breaches, can always get worse depending upon how your company reacts to them.

Additionally, you should consider performing privacy impact assessments for all new projects prior to the regulations coming into force. What personal data will the project involve? What are the risks involved for that project? what will compliance look like for that project?

You may also consider checking your insurance coverage in the event of such a breach.

Additionally, you should consider performing privacy impact assessments for all new projects prior to the regulations coming into force. What personal data will the project involve? What are the risks involved for that project? what will compliance look like for that project?

You may also consider checking your insurance coverage in the event of such a breach.

If you start scheduling some of the above activities into the diary of your business now you will put that business in a better position to be able to be able to 'beat the rush' which will inevitably occur as we near the 2018 deadline.

There are two other things to be aware of on the subject of these regulations -

There are two other things to be aware of on the subject of these regulations -

Impact of Brexit

Any UK company processing data relating to selling goods or services to EU citizens will need to comply with the regulations, regardless of what happens in respect of Brexit. It is also possible, one might say probable, that the UK government will choose to port over the regulations in order to: shortcut the development of alternative regulations; and maintain a system whereby data can be exchanged between the UK and the EU easily.

Artificial intelligence

Elizabeth Denham, the UK Information Commissioner, recently published a paper on the ICO website which reviews the implications of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning for data protection. The concern being that if an AI is processing data, and learning and altering its data processing as it does so, how can it be guaranteed that the AI will do so within the data protection regulations framework. That paper concluded with six key recommendations, that big data analysis should: avoid the use of personal data where possible and anonymise that data; ensure that the processing is transparent; perform privacy impact assessments as a routine element of the process; adopt a privacy by design approach as mentioned above; develop and use an ethical principles policy; and develop auditable machine learning algorithms.

Interestingly, what that paper did not do was address how data protection regulations apply to the personal data of AIs. This perhaps seems an amusing, if not trivial, statement to make at present, but, given the expectation that AI will exceed the human mind this century - perhaps even the first half of this century, we should probably be considering the impact of AI on legislation and vice-versa. Think on this for a moment, the data that relates to an AI will not be covered by these regulations unless it can also identify an individual human. So, an IP address that relates solely to your Foodie-Bot ™ will only be protected if it also relates to you. If your SociBot ™ is busy posting social updates on the next generation of social networks, those posts will also not be protected, unless they also relate to you. If your IBank-BankyBot ™ has its own bank account, those details are not covered, unless they also relate to you. That last fanciful example is timely given the recent prediction by banks that AI will be running human/bank interactions within three years. Legislation is almost always behind technology; at some stage, probably fairly shortly, we will need to start considering how our current legislation fits with an AI world; as we noted in our recent article on copyright, if your BanksyBot ™ paints a wall mural it will not be worth $1million as it will be able to be copied by all and sundry – well, bad luck - 'its' personal data won't be protected either.

Interestingly, what that paper did not do was address how data protection regulations apply to the personal data of AIs. This perhaps seems an amusing, if not trivial, statement to make at present, but, given the expectation that AI will exceed the human mind this century - perhaps even the first half of this century, we should probably be considering the impact of AI on legislation and vice-versa. Think on this for a moment, the data that relates to an AI will not be covered by these regulations unless it can also identify an individual human. So, an IP address that relates solely to your Foodie-Bot ™ will only be protected if it also relates to you. If your SociBot ™ is busy posting social updates on the next generation of social networks, those posts will also not be protected, unless they also relate to you. If your IBank-BankyBot ™ has its own bank account, those details are not covered, unless they also relate to you. That last fanciful example is timely given the recent prediction by banks that AI will be running human/bank interactions within three years. Legislation is almost always behind technology; at some stage, probably fairly shortly, we will need to start considering how our current legislation fits with an AI world; as we noted in our recent article on copyright, if your BanksyBot ™ paints a wall mural it will not be worth $1million as it will be able to be copied by all and sundry – well, bad luck - 'its' personal data won't be protected either.

As stated above, HPLpro can of course provide a freelance in-house lawyer to help you with your data protection requirements on a part time, short-term or project by project basis. Our freelancers could help you map your data, train your people, perform dry run data breach exercises, or they could even help put in place consent certification mechanisms and policies – just let us know your needs. Detailed guidance on a lot of the above areas will certainly be released by the regulatory authorities and we will post more articles on this subject as and when that guidance lands.

Cheers

HPLpro Team

Cheers

HPLpro Team

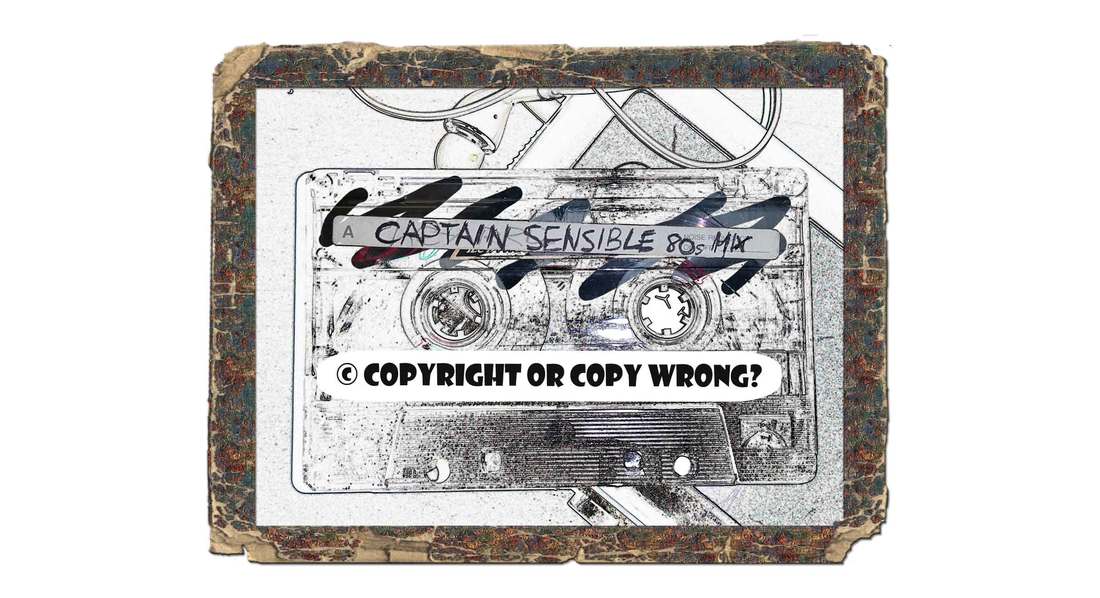

This article follows up on our hugely popular article on the basics of intellectual property with a slightly more detailed look at copyright. In this article we we examine what copyright is, what it does and how it is surviving in the modern digital era.

As always, it is worth restating that HPLpro is not a legal firm, and this article should not be taken as legal advice. It is important for you and your business to have experienced legal practitioners review your business ideas and intellectual property portfolio to ensure that they adequately meet your needs. Please feel free to request a freelance in-house lawyer from us if required.

As always, it is worth restating that HPLpro is not a legal firm, and this article should not be taken as legal advice. It is important for you and your business to have experienced legal practitioners review your business ideas and intellectual property portfolio to ensure that they adequately meet your needs. Please feel free to request a freelance in-house lawyer from us if required.

Summary

© Copyright protects creative works;

© it does not protect ideas; © there are exceptions to copyright; © some copyright protections are global; © copyright expires after a certain time; and © technology is changing faster than the law. |

As stated in our earlier article, copyright is essentially the protection of rights in creative works – think pictures, music, sculptures, graphics, films, books, and so on. In essence, it gives the holder of those rights the ability to prevent other people copying the work, or using the work in certain ways without permission. Importantly, copyright does not protect ideas – it protects the expression of those ideas, which need to exist in some tangible form. For example, the music created by a band who are jamming will not have copyright protection unless that music is recorded in some form. The same is true of a sculpture, copyright is only available once the sculpture has been created, rather than when it is an idea in the head of the sculptor.

However, it is important to distinguish between the rights in an expression of an idea and the rights in a physical object - copyright does not necessarily also mean that you own the physical object that 'holds' the copyright. For example, the band Gorillaz own the copyright to the song 'Superfast Jellyfish' but that does not equate to automatic ownership of every CD with the song on. The opposite is also true, you can own a CD with 'Superfast Jellyfish' on it without having the rights to commercially exploit that song.

"Hang on," we hear some of you cry, "I just recorded my 7 inch record of Captain Sensible's 'Happy Talk' onto a TDK Cassette tape. Am I going to go to prison?" Perhaps, for the music choice (Captain Sensible should go to prison for that video), but as for copyright, there are exceptions to copyright – which are covered later in this article – which mean that in some territories (such as the UK) you are able to copy the artistic work in certain circumstances – such as making copies for personal use. Interestingly, that change only occurred in the UK in 2014 and essentially reflected what the public were already doing with those copyright works; mixtapes made prior to 2014 in the UK were technically infringing copyright.

Berne baby, Berne

As noted in our previous article, the details of copyright change from country to country – copyright is not international - however, the Berne Convention, which was established in 1886 and has been gently amended over the years, creates certain minimum requirements of protection for the territories that have signed up to it (all 173 of them). The Convention holds that if you created a work which qualifies for protection in one of the contracting states, you get the same minimum level of protection in all of the others - and that protection is not conditional (in other words, it is automatic).

This means that, in respect of the beautiful photograph above, if it were to qualify for copyright protection in the UK, it would, for example, get copyright protection in Nigeria.

The Berne Convention also holds that there are two distinct elements to copyright – economic and moral rights – and those rights can be held by different persons or entities. Economic rights are what we normally think of when considering copyright – they grant the owner the ability to exploit the copyright for financial gain and prevent others from doing so – in other words the owner has the right to copy and sell (or license) the work. Moral rights are slightly different – they enable the author of the work to be recognised as the author; and grant the ability to prevent the work being modified in a way that would be prejudicial to the honour or reputation of the author. In many 'western' countries, moral rights are seen as the ugly cousin of economic rights and can even be waived in certain territories, such as the UK. the waiver of moral rights is, however, considered by some to be controversial as, if there is an imbalance in negotiating power, an artist may be unduly 'encouraged' to waive those rights. On the other hand, a company will simply use a different freelancer should the proposed artist object, hence the controversy. Perhaps a reasonable approach to take would be to suggest that, if the artist is merely bringing into existence somebody else's vision, then they should not object to waiving moral rights. Of course, if the work of art is solely the vision of the artist, it would seem unreasonable to expect the artist to waive their moral rights.

The Berne Convention also holds that there are two distinct elements to copyright – economic and moral rights – and those rights can be held by different persons or entities. Economic rights are what we normally think of when considering copyright – they grant the owner the ability to exploit the copyright for financial gain and prevent others from doing so – in other words the owner has the right to copy and sell (or license) the work. Moral rights are slightly different – they enable the author of the work to be recognised as the author; and grant the ability to prevent the work being modified in a way that would be prejudicial to the honour or reputation of the author. In many 'western' countries, moral rights are seen as the ugly cousin of economic rights and can even be waived in certain territories, such as the UK. the waiver of moral rights is, however, considered by some to be controversial as, if there is an imbalance in negotiating power, an artist may be unduly 'encouraged' to waive those rights. On the other hand, a company will simply use a different freelancer should the proposed artist object, hence the controversy. Perhaps a reasonable approach to take would be to suggest that, if the artist is merely bringing into existence somebody else's vision, then they should not object to waiving moral rights. Of course, if the work of art is solely the vision of the artist, it would seem unreasonable to expect the artist to waive their moral rights.

As stated above, copyright normally arises automatically upon the creation of the artistic work. There is not a register of copyright works in the UK – when you create it, copyright arises immediately and automatically. There is however a register of copyright works in the US and, in general, you cannot sue for copyright infringement in the US unless your copyright is registered at the US Copyright Office. The good news is that you can register the copyright yourself at the US Copyright Office.

We mentioned in our previous article that copyright only last for a period of time and then expires. The Berne Convention states that the minimum period is the life of the author and then a period of 50 years following the death of the author. In many countries, that period is extended to 70 years plus the life of the author.

Exceptions to the rule

So what can a non-copyright holder do with an artistic work that is protected by copyright?

Good question. In many territories, there are exceptions to copyright (although these vary greatly from country to country). Common exceptions are for research purposes, personal use, private study, criticism/review, teaching, parody and so on. Most of the exceptions deal with permissible reproduction of the copyright work in ways which do not have a commercial purpose, but that is not always necessarily the case – copyright infringement can take place even if money is not being exchanged.

Another way of using a copyright protected work without infringing it is to obtain a license to do so. That license could either be general (in other words, everybody is offered the same license on the same terms), or specific to you as an individual (such as in the case of music sample clearances as detailed below). These licenses impact upon all of us more often that we may realise, for example, computer software licenses are likely to be the general copyright licenses that most people will encounter in their daily lives. We know you've all clicked 'I agree' without reading the accompanying license at some stage or another. Another common license in the UK is the use of a radio in a public place, such as an office, which is also likely to require a copyright license.

Good question. In many territories, there are exceptions to copyright (although these vary greatly from country to country). Common exceptions are for research purposes, personal use, private study, criticism/review, teaching, parody and so on. Most of the exceptions deal with permissible reproduction of the copyright work in ways which do not have a commercial purpose, but that is not always necessarily the case – copyright infringement can take place even if money is not being exchanged.

Another way of using a copyright protected work without infringing it is to obtain a license to do so. That license could either be general (in other words, everybody is offered the same license on the same terms), or specific to you as an individual (such as in the case of music sample clearances as detailed below). These licenses impact upon all of us more often that we may realise, for example, computer software licenses are likely to be the general copyright licenses that most people will encounter in their daily lives. We know you've all clicked 'I agree' without reading the accompanying license at some stage or another. Another common license in the UK is the use of a radio in a public place, such as an office, which is also likely to require a copyright license.

Copyright Notice

You may recognise the copyright symbol - ©. It is not necessary to use but indicates to the world that you consider the work to be protectable and yours. You may have also seen dates feature after a copyright notice – this gives the viewer the knowledge of when a copyright piece was first created or published. In the years prior to 2000 a particular global treaty required the words 'All Rights Reserved' to be written on the copyright work in order to be able to have protection but that is no longer the case – however, you will see that it is almost always still used in literature and on websites – we still use it at the footer of most of our webpages – such as on our home page - for example. Old habits die hard, although it is good practice to nevertheless use a copyright notice. An example of a simple notice is: "© Copyright HPLpro Limited 2017. All Rights reserved. "

The Law moves slowly...

We have dealt with some of the main elements of copyright in the preceding paragraphs. Now let us look at how the law is interacting with the modern world when it comes to copyright. We made reference to animal selfies in our earlier article which have recently been held by a court in the US to not attract copyright – animal art has been a thing since the 1950's if not before, so it goes to show how slowly the law gets around to considering new developments. Speaking of non-human artistic works, presumably the same applies to AI meaning that, when the AI in your Google piano gets advanced enough to invent its own music, that music would not give rise to copyright protection. Which brings us neatly on to technology.

The World Intellectual Property Organisation – which is the body that manages the Berne Convention – is also responsible for the 1996 WIPO Copyright Treaty. This treaty is a special agreement under the Berne Convention that deals with digital elements of copyright protection in relation to computer programmes and databases.

Given that computer programmes and databases existed for decades before the WCT treaty it again goes to show how slow legislation moves in respect of keeping up with the pace of technological change; perhaps necessarily, given the pace of technology, legislation is behind the curve when it comes to the modern digital world. Legislators, lawyers and courts often find themselves trying to shoehorn matters relating to new technology into old laws.

What would the authors of the Berne Convention make of a live broadcast of a band on Google Hangouts, where the band are all in different countries (some of which being non-WCT and non-Berne countries) – where the drummer is Biff-Biff the monkey, the bassist is Ceolopithia, a character in World of Warcraft (being played by a real human), an MIT Artificial Intelligence, Robot X1, is playing the guitar, Beardy Man is on vocals and samples from various bands from the 1980s are being mixed in by Dr Dre . The performance is being watched, recorded and broadcast on a multitude of different devices – including on a big screen at Time Square in New York (with the crowd recording that broadcast on their phones). Additionally, the score for the music is being automatically ascribed by a Google AI app (we may have just invented that) on at least a million Samsung phones. Finally, there is no contract between the band as they have never met and are just jamming. What would the law make of that? Either way, we want that album. What would the band be called, we wonder…

What would the authors of the Berne Convention make of a live broadcast of a band on Google Hangouts, where the band are all in different countries (some of which being non-WCT and non-Berne countries) – where the drummer is Biff-Biff the monkey, the bassist is Ceolopithia, a character in World of Warcraft (being played by a real human), an MIT Artificial Intelligence, Robot X1, is playing the guitar, Beardy Man is on vocals and samples from various bands from the 1980s are being mixed in by Dr Dre . The performance is being watched, recorded and broadcast on a multitude of different devices – including on a big screen at Time Square in New York (with the crowd recording that broadcast on their phones). Additionally, the score for the music is being automatically ascribed by a Google AI app (we may have just invented that) on at least a million Samsung phones. Finally, there is no contract between the band as they have never met and are just jamming. What would the law make of that? Either way, we want that album. What would the band be called, we wonder…

…but The Internet moves so quickly

Never one to hang around, The Internet is trying to come up with its own solutions to the above conundrums, primarily taking the approach that everyone can use everything. In particular, the Creative Commons licenses enable users to copy, edit, alter, update and generally fiddle with the creative works which the creators have licensed – for free - for that purpose, all within the bounds of copyright laws. The Creative Commons ethos is, "when we share, everyone wins." Interestingly, a key factor of the CC license is that of accreditation - you can use the author's work provided that you also state where the work originally came from.

Of course, The Internet also has a habit of ignoring rules and laws altogether.

In many ways, The Internet has collided head on with copyright, particularly in relation to films, music and software. The fallacy that a person can sit behind their computer screen and nobody can 'see' what they are doing is like that of a child with a box on their head thinking that nobody can see them.

The reality is more one of cost – whilst online copyright infringement can usually be traced, it is unlikely to be punished, simply due to the disproportionate cost involved; pursuing a person who has downloaded a Dizzee Rascal album in breach of copyright will cost more than the price of the album itself. Additionally, legal systems would not be able to cope with the large numbers of claims that would arise. Finally, depending upon the territory, the copyright holder will also likely need to show a loss to base their claim on. If the Dizzee Rascal downloader bought a copy of the album when challenged there would likely be no basis for a claim. The complaining party also has to have the right to bring the case, as Osama Fahmy found when he brought a US copyright claim against Jay-Z for the use of some of his uncles' music in the 1999 song, 'Big Pimpin’.'

There is no question that with the march of the online world the approach to copyright of a significant proportion of the population has changed, its importance has perhaps diminished in the eyes of some. Nevertheless, it is perhaps unfair to solely blame The Internet; piracy, the glamourous name given to unauthorised reproduction of copyright works, had been around for decades prior to The Internet. Many readers of this article may recall making mixtapes and perhaps going on to sell them at school. The financial element is important here; whilst the law perhaps does not reflect it, in practice, copyright holders seem to be targeting those persons and entities who are making money out of copyright infringement or who are enabling others to commit copyright infringement rather than pursuing the bedroom Dizzee Rascal downloaders. Further, plagiarism (the practice of copying someone's work and passing it of as your own - synonymous with copyright theft) has been around for centuries; it is arguably a little easier to commit plagiary with the advent of The Internet but also a little harder to get away with.

Frankly, it is getting physically easier to copy stuff; we can even print plastic copies of virtually anything in our own homes. Additionally, the line between what is and what is not copyright infringement is becoming increasingly blurred given the increasing sophistication of technology and it is all happening at a pace which outstrips the law, cases and legislation. The use of samples in music has been a phenomenon for many decades but could technically be an infringement of copyright, notwithstanding the result of the 'Big Pimpin'' case highlighted above. In fact, there have been numerous cases since the 1990s (way too many to list in this article) , particularly in the US, on this subject. This all means that advice from lawyers is therefore becoming an increasingly valuable commodity when it comes to copyright and copyright infringement and avoiding court cases.

Does that mean however, that an artist should talk to their lawyer prior to letting their creative juices flow? Whilst that is something for each individual and entity to decide for themselves, it would be prudent to keep your freelance HPLpro lawyer close to hand when your company starts producing copyright works, just in case. Lawyers can be creative too don't you know.

Feel free to comment on how copyright operates in your specific country.

We hope you found the above useful; let us know if you have any other request for articles. Stay tuned for other articles on IP, contracts and other interesting legal things!

The HPLpro team

We hope you found the above useful; let us know if you have any other request for articles. Stay tuned for other articles on IP, contracts and other interesting legal things!

The HPLpro team

In the latest of articles from our freelancers on certain areas of law, we tackle the basics of intellectual property (also called IP): what it is, what types of IP there are and some helpful things to think about.

As always, it is worth restating that HPLpro is not a legal firm, and this article should not be taken as legal advice. It is important for you and your business to have experienced legal practitioners review your business ideas and intellectual property portfolio to ensure that they adequately meet your needs. Please feel free to request a freelance in-house lawyer from us if required.

As always, it is worth restating that HPLpro is not a legal firm, and this article should not be taken as legal advice. It is important for you and your business to have experienced legal practitioners review your business ideas and intellectual property portfolio to ensure that they adequately meet your needs. Please feel free to request a freelance in-house lawyer from us if required.

What is IP?

Intellectual property is an idea that has been turned into something; ideas on their own are not intellectual property. So, for example, you may think of an idea for a great painting which, in itself, is not intellectual property. However, as soon as you paint the painting you have created some intellectual property!

There are various types of intellectual property that you will have heard of (copyright, patents, trademarks, design rights, and so on) and we will detail those below. How these types of intellectual property are dealt with can change from country to country and some even have global agreements on how they work. Some types of intellectual property arise automatically and immediately upon creation whereas other types of intellectual property need to be registered – at a cost - with one or several governmental bodies in order to be protected. This article will focus on IP generally rather than the rules in any specific territory or country – it is always worthwhile engaging experts in the relevant area to ensure that you protected.

IP can be owned by individuals and companies and can be transferred from person to person or company to company; you do not need to be the creator of the IP to be the owner. IP can also be licensed from one party to another, so, in certain circumstances you can use someone else's IP under a license agreement. You can also have joint owners of IP.

It is worth bearing in mind that most IP only exists for a certain period of time (although in some instances those periods of time can be extended or renewed).

There are various types of intellectual property that you will have heard of (copyright, patents, trademarks, design rights, and so on) and we will detail those below. How these types of intellectual property are dealt with can change from country to country and some even have global agreements on how they work. Some types of intellectual property arise automatically and immediately upon creation whereas other types of intellectual property need to be registered – at a cost - with one or several governmental bodies in order to be protected. This article will focus on IP generally rather than the rules in any specific territory or country – it is always worthwhile engaging experts in the relevant area to ensure that you protected.

IP can be owned by individuals and companies and can be transferred from person to person or company to company; you do not need to be the creator of the IP to be the owner. IP can also be licensed from one party to another, so, in certain circumstances you can use someone else's IP under a license agreement. You can also have joint owners of IP.

It is worth bearing in mind that most IP only exists for a certain period of time (although in some instances those periods of time can be extended or renewed).

|

If you have an idea but have not yet turned it into actual IP – be sure to keep that information secret! As stated in this article, an idea on its own is not intellectual property – and you may find that you lose the ability to protect your idea if you don't keep it secret. If you need to tell other people or companies about your idea, make sure you use an NDA (aka confidentiality agreement) beforehand – see our explainer on NDAs and our free NDA builder.

|

Copyright

Copyright is essentially the protection of creative works – it protects the expression of an idea. So, for example paintings can be protected by copyright, as can statues, photographs, novels, drawings, computer programmes and so on. The key however is that these elements need to exist in the real world and need to have an element of creativity – meaning that, for example, the book needs to have actually been written down for it to attract copyright protection. The protection that copyright grants is the ability to stop someone else copying your work, adapting it, distributing it, or performing it without permission (if it is a play or musical score). We will look at copyright in more detail in our next article.

|

Patents

Patents deal with inventions and protect how and when other people can use that invention. A significant consideration with regard to patents is that they are published and are able to be freely viewed by everyone when they are registered. That means that somebody could take your invention and improve it and/or do it differently all potentially without infringing your patent. So, if you have something that is highly confidential, you may not want to have it published as a patent. Further, patents exist for a certain period of time, normally 20 years, after which time they pass into the public domain – so again, if you want more than 20 years of protection you may want to consider keeping the information a secret rather than registering a patent. However, to do so would be counteractive to the general philosophy of patents which is to encourage the development and sharing of new ideas. As with copyright, we will take a further look at patents in a later article.

| When hiring freelancers of any sort to turn your ideas into actual things – web designer, software programmer, artist, writer - remember to include language about IP ownership and to transfer that IP over to you or your company in the contract that you have with the freelancer. Depending upon where you are in the world, failure to do so could result in the IP being owned by the freelancer! If we get enough interest, we may ask one of our freelancers to create a free freelance template for download. Also note that if you are an employer, you should include appropriate language in your employment contracts on IP ownership. |

Trademarks

Trademarks protect branding which is used in relation to trade (and all of the trademarks in the above picture are used without permission - no challenge to their status intended.). Normally a trademark will be a word or a logo but in some territories worldwide you can also claim colours or smells as trademarks. A trademark is therefore a logo, word or other element which identifies the source of that logo or mark for the economic benefit of the owner but also for the benefit of consumers at large; if everyone could use the word Microsoft in respect of computer programmes that they were selling, users would have no idea of the origin, and therefore the quality (or lack of), of that software.

Trademarks can either be registered or unregistered depending upon the territory and the owner of the mark will have different remedies available depending upon the registration. Further, to complicate things slightly, trademarks exist in 'classes' which is a way of dividing those marks into categories of use. For example, Class 34 refers to tobacco and articles for smoking. That means that HPLpro could own a trademark for the word 'Cobra' in class 34 and that mark is not likely to infringe a 'Cobra' word trademark in class 39 – transport.

As with the other types of IP we will pen a further article on this subject at a later date.

Trademarks can either be registered or unregistered depending upon the territory and the owner of the mark will have different remedies available depending upon the registration. Further, to complicate things slightly, trademarks exist in 'classes' which is a way of dividing those marks into categories of use. For example, Class 34 refers to tobacco and articles for smoking. That means that HPLpro could own a trademark for the word 'Cobra' in class 34 and that mark is not likely to infringe a 'Cobra' word trademark in class 39 – transport.

As with the other types of IP we will pen a further article on this subject at a later date.

Design rights/ Registered designs/industrial designs

| This little bundle of IP rights varies greatly depending upon the country but in general they protect the aesthetics of an industrial article, particularly the design of that article. They may help you to prevent someone making, selling or distributing infringing articles. The classic design of an Alessi kettle for example may be the perfect subject for a registered design. |

Other IP

There are a few other elements which are sometimes considered to be intellectual property and are worthy of mention:

Trade secrets – these are confidential pieces of information which relate to the most vital elements of a business and normally they will be contained in the heads of only a few people worldwide. The Coca Cola recipe is rumoured to be one such trade secret.

Domain names – domain names can be considered to be intellectual property in that they can be owned and traded and are not physical items as such. Along with other IP elements, businesses should consider domains names as part of their intellectual property strategy.

Protected Geographical Location rights – the ability to refer to ther origin of a product or service can have real world value – Melton Mowbray pork pies for example. Although geographical locations are rarely owned by one business, nevertheless they can be exploited only by businesses operating in that area. Only pork pies made in the Melton Mowbray area can use such a reference on their packaging – even if they are identical in every way to one made just outside the area (aficionados will however tell you that the MM Pork Pie is distinctly different to all others).

Trade secrets – these are confidential pieces of information which relate to the most vital elements of a business and normally they will be contained in the heads of only a few people worldwide. The Coca Cola recipe is rumoured to be one such trade secret.

Domain names – domain names can be considered to be intellectual property in that they can be owned and traded and are not physical items as such. Along with other IP elements, businesses should consider domains names as part of their intellectual property strategy.

Protected Geographical Location rights – the ability to refer to ther origin of a product or service can have real world value – Melton Mowbray pork pies for example. Although geographical locations are rarely owned by one business, nevertheless they can be exploited only by businesses operating in that area. Only pork pies made in the Melton Mowbray area can use such a reference on their packaging – even if they are identical in every way to one made just outside the area (aficionados will however tell you that the MM Pork Pie is distinctly different to all others).

Company names – finally a company name is intellectual property of a sort and it is worth bearing in mind that just because you own the company name does not mean that you own a trademark with the same name nor does it give you automatic rights to a domain name.

Hope you found the above useful. We will tackle the specific elements mentioned above in later articles, so keep tuned!

The HPLpro team

The HPLpro team

In the next of our series of explanatory articles on commercial legal issues, we asked one of the freelancers who works with us to put some thought into explaining Force Majeure.

As always, it is worth restating that HPLpro is not a legal firm, and this article should not be taken as legal advice. It is important for you and your business to have experienced legal practitioners review any legal issues or documents to ensure that they adequately meet your needs. Please feel free to request a freelance in-house lawyer from us if required.

As always, it is worth restating that HPLpro is not a legal firm, and this article should not be taken as legal advice. It is important for you and your business to have experienced legal practitioners review any legal issues or documents to ensure that they adequately meet your needs. Please feel free to request a freelance in-house lawyer from us if required.

What could possibly go wrong?

Force Majeure is a term that is related to contracts, so if you have no interest in contracts it is probably best that you look away now. For the rest of you who are keen to understand this peculiar term, read on!

Putting it simply – and this will be a very simplified explanation given the space – force majeure is a list of disasters. Specifically, it is a list of disasters which, if they arise, mean that a party to the contract may be allowed to be in breach of that contract. The point of force majeure clauses is to attempt take a reasonable approach to apportioning risk in a contract for certain events: which party should bear the risk of a certain disaster happening. Common events are: fire, flood, strike, armed insurrection, war, and so on. You may have also seen 'act of god,' listed in a force majeure clause and in modern parlance it is best thinking of this phrase as meaning a natural disaster such as a flood or lightning strike.

Putting it simply – and this will be a very simplified explanation given the space – force majeure is a list of disasters. Specifically, it is a list of disasters which, if they arise, mean that a party to the contract may be allowed to be in breach of that contract. The point of force majeure clauses is to attempt take a reasonable approach to apportioning risk in a contract for certain events: which party should bear the risk of a certain disaster happening. Common events are: fire, flood, strike, armed insurrection, war, and so on. You may have also seen 'act of god,' listed in a force majeure clause and in modern parlance it is best thinking of this phrase as meaning a natural disaster such as a flood or lightning strike.

Consider this: if an earthquake delays a supplier of chemicals making a delivery to their customer, that delay will likely have a real cost to the customer (it may even put them in breach of other contracts). Without a force majeure clause in a contract, the supplier is likely to be responsible for the costs of delay; with a force majeure clause inserted the supplier is likely to be able to use that clause to excuse their breach meaning that the customer will pay the costs of the delay. Which position is fairer? Should the customer or the supplier feel the pain of an earthquake that was the fault or neither party? It is hard to say really as neither party caused the earthquake and neither party could control the effects of the earthquake.

Out of Control

Which brings us neatly on to the next element of force majeure clauses: the concept of reasonable control. In most force majeure clauses, you are likely to see the phrase, "Beyond that party's reasonable control". This is a reference to the outside influence of a disaster - neither party could control that disaster. The use of the word 'reasonable' in this phrase is an attempt to limit the extent of what is considered control.

For example, flooding is a common disaster that you may see listed in a force majeure clause; the week after the above earthquake, the unlucky supplier's factory got flooded meaning more delays for their customers and more cost. Oh dear. Classic force majeure. Nothing could have been done about a flood, right? Wrong; it just so happens that the supplier has a flood control system at the factory that was not activated at the time of the flood because it made a whirring noise that irritated the plant manager. Had it been activated, the flood would not have happened. The means of averting the disaster was in the supplier's control, meaning that it is only fair that the supplier bears the cost of the delay.

May the Force - Majeure - be with you

So, force majeure clauses are an attempt to apportion risk for external events in a contract. Whilst, on the face of it, the force majeure clause is fairly bland, standard and uninspiring, it can often be a secret battle ground between supplier and procurer who tend to want to move the risk dial toward the other party. If you are a vendor you may want that disaster list to be as comprehensive as possible. On the other hand, if you are buying a product or a service, it is highly likely that the party that you are buying from will have included a long and wide ranging list of disasters in the force majeure clause. In fact, some elements may not be a disaster at all, so it is vitally important to have a legally trained person consider the details of the language of your contracts as small changes can have a major impact. For example, a clause may list 'illness' as an event under the force majeure clause. What would the impact of that be? The author of this piece has seen: 'objects falling out of planes' listed in a force majeure clause as well as 'inclement weather'.

What happens next?

The actual effect of the clause will differ depending upon the wording of the clause itself. Normally, the party relying on the force majeure clause will be excused from their breach of contract for as long as the force majeure event interrupts their performance of the contract, but that is not necessarily always going to be the case and again, having a legally trained person review those clauses is vital. For example, a clause may require the party relying on the clause to notify the other party of the event within a particular timeframe and, if they don't, they may lose the right to rely on the clause.

Additionally, a clause may contain a right for the party not affected by the force majeure event to terminate the contract if the event lasts for more than, say, a month. In the absence of such a clause, the parties may become stuck in a contract that cannot be performed due to a disaster, the risk for which rests solely on the shoulders of one party.

Additionally, a clause may contain a right for the party not affected by the force majeure event to terminate the contract if the event lasts for more than, say, a month. In the absence of such a clause, the parties may become stuck in a contract that cannot be performed due to a disaster, the risk for which rests solely on the shoulders of one party.

Of course, the presence of a force majeure clause doesn’t always mean that the party relying on it can get off scot free – that will depend upon the details of the clause itself and the law of the jurisdiction that governs the contract. Force majeure clauses can be highly controversial and may not always be upheld by a court as being enforceable. For example, courts in England and Wales are not likely to agree that economic hardship is a valid force majeure event, even if a contract says that it is. What will or will not be acceptable as a force majeure event will be different from country to country.

Check the Small Print

On the other hand, what is enforceable and what is written into a contract are not always the same thing. After all, you can persuade a party to a contract that you are right without having to go to court. This means that the details of the clause are important and can have a significant impact. For example, if a clause simply references 'beyond that party's control,' instead of 'beyond that party's reasonable control,' that could have a significant influence on the outcome of the clause.

Further, some clauses require the force majeure event to be unforeseen which adds a whole extra layer of complication; what does foreseen mean in the context of a flood, strike or terrorist attack? The answer will depend upon the specific circumstances of the contract and the event itself.

Even taking the above into account, force majeure clauses are often overlooked by businesses and lawyers because in many instances they will be bland and uninteresting. Every now and then, however, something more interesting pops up so it always pays to be vigilant particularly as some force majeure events may be uninsurable.

Finally, and this is something that we will revisit in a later article on contract management, it is worthwhile making sure that the force majeure clauses that your business agrees to in its procurement contracts are matched in your sales contracts. Otherwise your business could be left holding the force majeure disaster baby.

Further, some clauses require the force majeure event to be unforeseen which adds a whole extra layer of complication; what does foreseen mean in the context of a flood, strike or terrorist attack? The answer will depend upon the specific circumstances of the contract and the event itself.

Even taking the above into account, force majeure clauses are often overlooked by businesses and lawyers because in many instances they will be bland and uninteresting. Every now and then, however, something more interesting pops up so it always pays to be vigilant particularly as some force majeure events may be uninsurable.

Finally, and this is something that we will revisit in a later article on contract management, it is worthwhile making sure that the force majeure clauses that your business agrees to in its procurement contracts are matched in your sales contracts. Otherwise your business could be left holding the force majeure disaster baby.

Let us know if you have any comments on the above or any exciting and interesting tales of Force Majeure!

Cheers

The HPLpro Team

Cheers

The HPLpro Team

After our extremely popular release of this free confidentiality agreement builder, we thought that it would be worthwhile to go into a little more depth on the subject of non-disclosure agreements.

But first, a little disclaimer: as always, it is worth restating that HPLpro is not a legal firm, and this article should not be taken as legal advice. It is important for you and your business to have experienced legal practitioners review any legal issues or documents to ensure that they adequately meet your needs. Please feel free to request a freelance in-house lawyer from us if required.

But first, a little disclaimer: as always, it is worth restating that HPLpro is not a legal firm, and this article should not be taken as legal advice. It is important for you and your business to have experienced legal practitioners review any legal issues or documents to ensure that they adequately meet your needs. Please feel free to request a freelance in-house lawyer from us if required.

Meaning of NDA